TL;DR

This forensics challenge provided a Linux ELF binary (cat) and its core dump, with the goal being to recover the flag passed as an input file (./flag.png). The initial code analysis revealed a memory leak where the binary continuously allocated heap chunks to read and store the file content but failed to free any of them, ensuring that the full file was preserved in the process’s heap memory at the moment of the crash. My solution involved loading the core dump into GDB, dumping the heap memory regions, and then writing a Python script to stitch the fragmented file contents back together by parsing the glibc heap metadata’s size fields. I reconstructed the file and extracted the flag from the resulting flag.png image.

Analysis

The challenge provides two files:

.

├── cat

└── core.39382

The binary’s purpose appears to be reading and printing the contents of a file, similar to the standard cat utility, but with a custom implementation.

Analyzing the decompiled main function reveals the core logic responsible for the crash:

int main(int argc,char **argv)

{

// ... variable declarations ...

if (argc != 2) {

puts("./cat [file]");

exit(1);

}

tVar2 = time(NULL);

srand(tVar2);

__fd = open(argv[1],0);

while( true ) {

iVar1 = rand();

__size = (iVar1 % 0x32) * 0x10 + 8;

__buf = malloc(__size);

sVar3 = read(__fd,__buf,__size);

if (sVar3 == 0) break;

write(1,__buf,__size);

}

free(::brk);

return 0;

}Instead of using a fixed buffer, this program dynamically allocates space for randomly sized chunks. The size is calculated using a random number modulo 50 (0x32), then multiplied and offset to ensure it’s always aligned to 8 bytes: (iVar1 % 0x32) * 0x10 + 8.

while( true ) {

iVar1 = rand();

__size = (iVar1 % 0x32) * 0x10 + 8;

__buf = malloc(__size);

sVar3 = read(__fd,__buf,__size);

if (sVar3 == 0) break;

write(1,__buf,__size);

}For every single piece of data it reads from the target file (read(__fd, __buf, __size)), it first calls malloc(__size). It then prints the chunk.

This behavior immediately sets off alarms. It’s a textbook memory leak! The program allocates dozens of chunks to hold the file contents, but it never calls free() inside the loop. When the program crashes after reading the entire file, the full content of the file we need to recover is guaranteed to be sitting in those un-freed heap blocks.

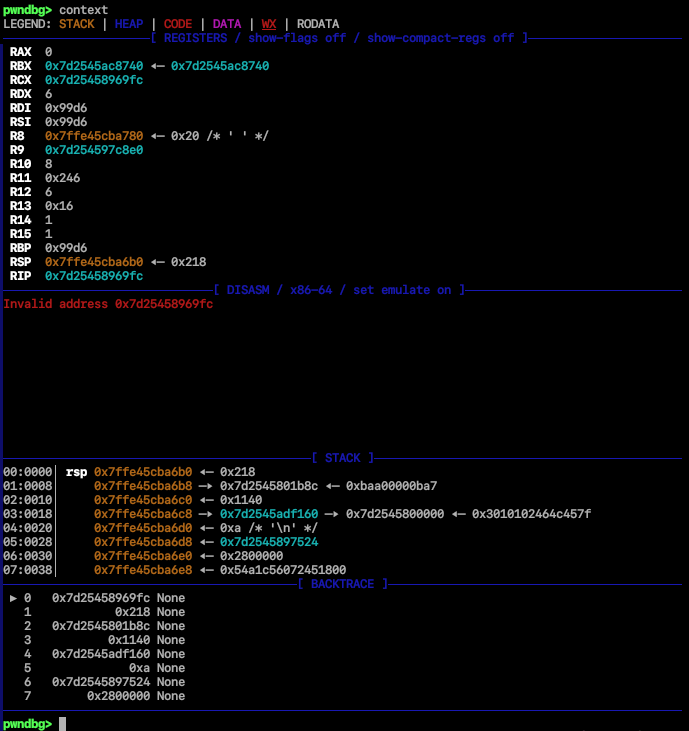

I loaded the executable and the core dump into GDB using the pwndbg extension.

# Usage: gdb <executable> <coredump>

$ gdb-pwndbg ./cat ./core.39382

I used info proc to inspect the process information stored in the dump:

pwndbg> info proc

exe = '/home/dog/Desktop/heap_exploitation/cat ./flag.png'

The program was executed on a file named ./flag.png. This confirmed that the un-freed data I was looking for was the content of a PNG image file, which was almost certainly a container for the flag.

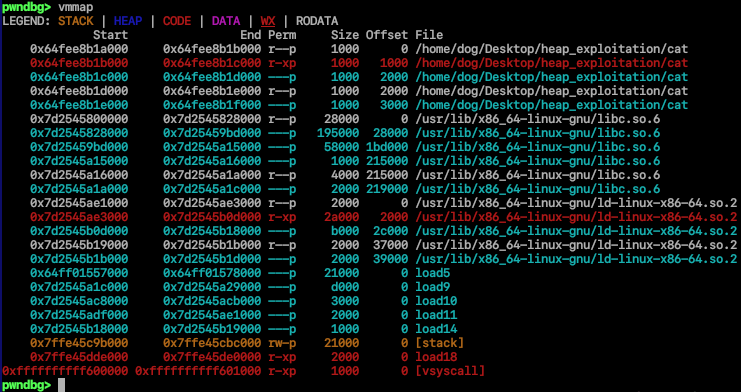

The next step was to examine the memory layout of the crashed process using vmmap. While a core dump often lacks complete virtual memory mapping information, I knew my target was the heap, as that’s where the file chunks were continuously allocated.

I identified the large, anonymous memory regions (loadX) which represented the dynamic memory, including the heap. To search for the PNG file’s content, I decided to dump these relevant memory segments to local files.

# Usage: dump memory <filename> <start_address> <stop_address>

pwndbg> dump memory load5 0x64ff01557000 0x64ff01578000

pwndbg> dump memory load9 0x7d2545a1c000 0x7d2545a29000

pwndbg> dump memory load10 0x7d2545ac8000 0x7d2545acb000

pwndbg> dump memory load11 0x7d2545adf000 0x7d2545ae1000

pwndbg> dump memory load14 0x7d2545b18000 0x7d2545b19000

pwndbg> dump memory stack 0x7ffe45c9b000 0x7ffe45cbc000 Since I knew the target was a PNG file, I searched the dumped segments for the file’s known magic bytes, the signature ‰PNG␍␊␚␊.

$ grep "PNG" -R .

grep: ./load5: binary file matches

grep: ./core.39382: binary file matchesThe load5 file showed a match. This confirmed that the beginning of the file (and thus the first series of un-freed heap chunks) was contained within this memory region. A quick hexdump of load5 verified this:

00000000: 0000000000000000 0000000000000291 ................

00000010: 0000000000000000 0000000000000000 ................

***

00000290: 0000000000000000 0000000000000301 ................

000002a0: 0a1a0a0d474e5089 524448490d000000 .PNG........IHDR

000002b0: 49010000a9040000 e95ddf0000000208 .......I......].

000002c0: 47527301000000cc 0000e91cceae0042 .....sRGB.......

000002d0: 0000414d41670400 00000561fc0b8fb1 ..gAMA......a...

000002e0: 0000735948700900 c701c30e0000c30e ..pHYs..........

000002f0: 492f36000064a86f bddded5e78544144 o.d..6/IDATx^...

00000300: 85b7e1c6dbb6dc95 982b158a24e1402d ........-@.$..+.

00000310: 2db402e016c3dfec 276281ddb09a9228 .......-(.....b'

00000320: 06e3e0755391c12e bee0ceeeccce1efc ...Su...........

00000330: 3aefe48240240201 b021f3e20935e24f ..$@...:O.5...!.

00000340: 0000003ffbffa31f 0000000000000000 ....?...........

***

We can also get the size of each section, this way we can find all sections from this single file, and reconstruct the flag, as you can see in this line:

00000290: 0000000000000000 0000000000000301 ................

The value 0x301 at offset 0x298 represented the size of the current heap chunk. The least significant bit (the 1 in 0x301) indicated that the previous chunk was still in use. By masking out that flag bit, I determined the actual size of this chunk was 0x300 bytes. This size information would be necessary for determining the boundaries of the flag file’s chunks and reconstructing the original flag.png file.

TIP

If you want to learn more about heap implementation in GLIBC I’d highly recommend this blog series by Azeria Labs: https://azeria-labs.com/heap-exploitation-part-1-understanding-the-glibc-heap-implementation/

Solution

Quick and dirty

Having confirmed that the un-freed data was segmented across many heap chunks, the next step was to automate the reconstruction process. Since the logic involves parsing raw heap metadata, I wrote a quick Python script to iterate through the dumped memory file (load5), read the chunk headers, extract the data, and stitch it all together.

import struct

heap = open("./load5", "rb")

read_size = lambda x: struct.unpack("<q", x)[0] & 0xfffffff0

# discard the first empty chunk

heap.read(8)

chunk_size = read_size(heap.read(8))

heap.read(chunk_size-8)

# I'll use this to store the chunks

chunks = []

while True:

try:

chunk_size = read_size(heap.read(8))

chunk_data = heap.read(chunk_size-8)

chunks.append((chunk_size,chunk_data))

print(f"read {chunk_size:#x} bytes")

except Exception as e:

print(f"error: {e}")

break

recovered_file = b"".join([t[1] for t in chunks])

with open("flag.png", "wb") as flag_file:

flag_file.write(recovered_file)I use read_size = lambda x: struct.unpack("<q", x)[0] & 0xfffffff0 to read a little-endian 64-bit integer, and then mask off the lowest 4 bits (specifically the PREV_INUSE flag) to get the true chunk size.

The data inside the chunk is the total chunk size minus the 16 bytes of metadata.

When I ran the script, it successfully parsed the majority of the chunks. The output showed the size of each heap chunk read:

read 0x300 bytes

read 0x110 bytes

read 0x230 bytes

read 0x210 bytes

read 0x20 bytes

read 0x160 bytes

read 0x110 bytes

read 0x1e0 bytes

read 0x90 bytes

read 0x190 bytes

read 0x1c0 bytes

read 0x1a0 bytes

read 0x20 bytes

read 0x190 bytes

read 0x220 bytes

read 0x240 bytes

read 0xb0 bytes

read 0x90 bytes

read 0x20 bytes

read 0x140 bytes

read 0xc0 bytes

read 0x2e0 bytes

read 0x290 bytes

read 0x1e0 bytes

read 0x120 bytes

read 0x140 bytes

read 0x130 bytes

read 0x320 bytes

read 0x290 bytes

read 0x1b0 bytes

read 0x80 bytes

read 0x260 bytes

read 0x2d0 bytes

read 0x2c0 bytes

read 0x140 bytes

read 0x2f0 bytes

read 0x100 bytes

read 0x1d1e0 bytesThe script produced a file, but when I tried to open the recovered flag.png, it was corrupted (as seen below).

Notice the highlighted lines in the script’s output. While the final, massive chunk (0x1d1e0 bytes) likely represents the remaining unallocated heap space after the file chunks, the real problem lay with the 0x20 byte chunks.

...

read 0x210 bytes

read 0x20 bytes // <--- Problematic

read 0x160 bytes

...

read 0x20 bytes // <--- Problematic

...

read 0x20 bytes // <--- ProblematicIn 64-bit glibc malloc, the smallest possible chunk is 0x20 bytes, which includes 16 bytes of metadata (prev_size and size) and 16 bytes of minimum user data (due to 16-byte alignment). The program’s random size formula, __size = (iVar1 % 0x32) * 0x10 + 8;,

can yield requested sizes like 0x8 or 0x18, both of which are below this minimum and will still result in a 0x20-byte chunk being allocated.

This explains why my initial reconstruction failed; for these three chunks, the actual data length was 0x8 or 0x18 bytes, but the allocator rounded them up to 0x20. The simplest way to resolve this ambiguity was a 2³ = 8 combination brute-force. I decided to write a small loop to try all eight possibilities, knowing that only one combination would yield a valid PNG file.

import struct

from itertools import product

heap = open("./load5", "rb")

read_size = lambda x: struct.unpack("<q", x)[0] & 0xfffffff0

# discard the first empty chunk

heap.read(8)

chunk_size = read_size(heap.read(8))

heap.read(chunk_size-8)

# I'll use this to store the chunks

chunks = []

while True:

try:

chunk_size = read_size(heap.read(8))

chunk_data = heap.read(chunk_size-8)

chunks.append((chunk_size,chunk_data))

print(f"read {chunk_size:#x} bytes")

except Exception as e:

print(f"error: {e}")

break

possible_sizes = list(product([0x8, 0x18], repeat=3))

possible_files = [b""] * len(possible_sizes)

print(f"possible solutions: {len(possible_sizes)}")

for i, possible_size in enumerate(possible_sizes):

chunk_id = 0

for size,data in chunks:

if size == 0x20:

possible_files[i] += data[ : possible_size[chunk_id] ]

chunk_id += 1

else:

possible_files[i] += data

for i, file in enumerate(possible_files):

with open(f"flag_{i}.png", "wb") as flag_file:

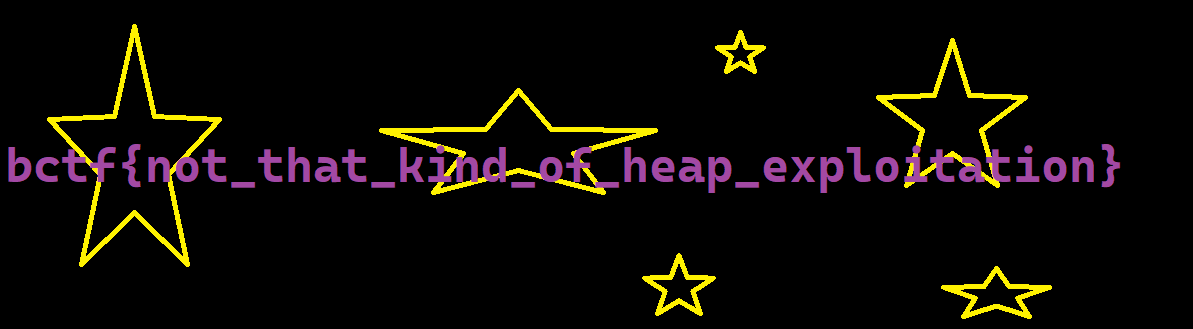

flag_file.write(file)And just like that here’s the flag:

Clean and thorough

A cleaner, more robust solution is to reconstruct the state of the program by finding the initial rand() seed. Since the initial size generation depends entirely on the seed, reversing it gives me all 37 original file read sizes perfectly, removing all guesswork.

From the decompilation, I knew the seed was generated using time(NULL). This meant I could brute-force timestamps near the time the CTF was running. I decided to check all timestamps from the current moment back to one month ago.

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <time.h>

/* sizes from of the heap chunks */

unsigned long target[] = {

0x2f8, 0x108, 0x228, 0x208, 0x18, 0x158, 0x108, 0x1d8, 0x88, 0x188, 0x1b8, 0x198, 0x18,

0x188, 0x218, 0x238, 0xa8, 0x88, 0x18, 0x138, 0xb8, 0x2d8, 0x288, 0x1d8, 0x118, 0x138,

0x128, 0x318, 0x288, 0x1a8, 0x78, 0x258, 0x2c8, 0x2b8, 0x138, 0x2e8, 0xf8

};

int check_seed(unsigned int seed) {

srand(seed);

for (int i = 0; i < 37; i++) {

int r = rand();

size_t size = ((r % 0x32) * 0x10 + 8);

// Target is the total HEAP CHUNK size, which is (Data Size + 16 bytes).

// I check if the generated DATA size is close to the expected target DATA size.

// I use a large margin (64 bytes) to tolerate any minor rounding/metadata issues

// that might have affected the target values I dumped from the core.

long diff = (long) size - (long) target[i];

if (diff < -64 || diff > 64) {

return 0;

}

}

return 1;

}

int main() {

time_t now = time(NULL);

time_t month_ago = now - (30 * 24 * 60 * 60);

printf("Bruteforcing seeds from %ld to %ld\n", month_ago, now);

for (time_t seed = month_ago; seed <= now; seed++) {

if (check_seed((unsigned int) seed)) {

printf("Found seed: %u (0x%x)\n", (unsigned int) seed, (unsigned int) seed);

printf("Time: %s", ctime(&seed));

return 0;

}

if ((seed - month_ago) % 100000 == 0) {

printf("Progress: %ld/%ld\n", seed - month_ago, now - month_ago);

}

}

printf("Seed not found\n");

return 1;

}As you can see on lines 17-22, since I didn’t know the exact 16-byte header offset for every dumped chunk, I used a large tolerance of ±64 bytes to check for a match. This was an approximation, but one based on the certainty that the random sequence had to match all 37 size calculations.

It only took a few seconds for the program to find the right timestamp:

Bruteforcing seeds from 1760187563 to 1762779563

Progress: 0/2592000

Progress: 100000/2592000

...

Progress: 2000000/2592000

Progress: 2100000/2592000

Found seed: 1762295820 (0x690a800c)

Time: Tue Nov 4 23:37:00 2025

Now that I got the seed it’s time to get the correct sizes, using this simple code:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

int main() {

int seed = 1762295820;

srand(seed);

for (int i = 0; i < 37; i++) {

int r = rand();

size_t size = ((r % 0x32) * 0x10 + 8);

printf("%#zx\n", size);

}

return 1;

}Now, all that’s left is to match these sizes with each heap chunk, as we did earlier. As you can see in the highlighted lines, they align perfectly with the results from the first method.

0x2f8

0x108

0x228

0x208

0x8

0x158

0x108

0x1d8

0x88

0x188

0x1b8

0x198

0x18

0x188

0x218

0x238

0xa8

0x88

0x18

0x138

0xb8

0x2d8

0x288

0x1d8

0x118

0x138

0x128

0x318

0x288

0x1a8

0x78

0x258

0x2c8

0x2b8

0x138

0x2e8

0xf8Since I only needed these three specific sizes, the first method (where I brute-forced through) turned out to be the more practical and time-saving approach. Still, this was a good learning exercise.

Conclusion

Ultimately, both methods; the brute-force and the seed reversal, would have led to the flag. The brute-force approach was clearly more efficient (just 8 quick attempts). But the seed reversal method gave me more understanding of the challenge and was a great exercise in forensic state reconstruction.

This was a cool challenge! It surprised me that it had only 21 solves in a 48-hour CTF, as it wasn’t conceptually difficult, just detail-oriented.